Grinding and shaping your knife is one of the most important tasks a knife maker will use. Every knife you make you will be ground and shaped. The technique you use will depend a lot on the equipment you have. I’ve also discovered Grinding a Custom Made Knife to be one of the hardest parts of knife making to learn on my own. Getting the bevel and plunge lines right is a struggle.

If you’re using files to shape the knife you should find the control easier, and if you’re using a belt grinder or sander with a heavy grit, you may find it best to switch to hand filing to get that control as the shape takes form.

Even with hand filing, there are options. Draw filing will give you the best control. In draw filing you hold the file like you would a draw knife and pull it towards you. This allows you to control the angle of the bevel better. Experience will tell you what works best for you. Moving back and forth between different types of shaping is also helpful when you’re trying to learn the ropes.

Once you’ve got the shape you want with a file, move to hand sanding. Wrap some sandpaper around a piece of wood or metal and work it just like you did with the file. Depending on how fine your last file was, you’ll probably start with around 80 or 100 grit and work up.

With a belt grinder (including a belt sander) you will need to learn the technique of grinding the bevel. With a typical knife shape, you want the strokes to be from side to side and completely horizontal. Resist the temptation to follow the curve of the blade. As your grinding you will need to add pressure with your thumb, pushing carefully into the bevel. In other words, if you need the bevel to climb higher on the blade, put more pressure higher on the bevel. If you think the bevel is climbing to fast and will go past your desired bevel line, put more pressure on the knife’s edge.

Using ceramic belts will actually help your grinding but add some risk as well. These belts are aggressive and fast cutting, so you need to remember to move up in grit with enough metal left to be removed to work into the shape you want. Because they cut fast it’s important to stay focused. Use light pressure when refining the bevel.

The line between taking too much metal and moving to the next grit to soon is a fine line that seems to only come with the experience. You will want to work through the grits up to the finish you desire. Make sure when you progress to the next grit all of the scratch marks are out from the previous grit. This holds true for both hand sanding and belt sanding. I find myself jumping back a grit or two because it’s easier and quicker when you realize you did not get all of the deeper scratches out.

A few tricks to help are alternating the scratch pattern. It’s easier to see the previous scratches if they are scored in a different direction. Another is etching or marking them with layout blue or black. I find with this technique you really need to alternate the pattern or the dark gets removed before the scratches do.

I typically grind to 120 or 220 grit before heat treatment. What grit you end with for final finish is purely a personal preference and depends on what type of finish you want. Experience and practice will help a great deal. Experiment and try different finishes (I have have in my first 100 knives) to give you your desired results.

Another area that requires experience is when to switch to a new belt. A new or newer belt will cut quicker and with less heat buildup. An older belt is less aggressive, will leave grooves less deep and heat the metal much faster. This makes the decision of when to use a newer or older belt somewhat of a challenge and again seems to require some experience.

Sharp angles on steel can wear out a belt quicker. Always start the grind with a used belt. This knocks the sharp edges off and your belts will last longer.

Wiping on some layout blue or etching in ferric chloride after each grit help you see if all of the previous scratches are gone. Also trying not grinding in the exact same angle helps. Turning the blade slightly to move the grind lines in a different angle help show the previous lines as they disappear.

Before heat treating the worry of over heating the blade is not an issue, but it’s good to also know that ceramic belts do not heat the steel as quickly, especially when they are new.

Lighting

Lighting is an important feature when you’re grinding and shaping your knife. You want light where you need light. Movable or flexible lights will help improve you grinding technique.

On your first few knives, switch to hand work more quickly. At first I found draw filing to work best for me before moving to sand paper.

At this point you don’t need to go to fine, depending on what your final finish will be, but going to 220 to 400 is a good idea.

Once again using the layout blue or etching between grits will benefit until you feel comfortable without it.

And don’t fear, after a few knives, and you’ve found the type of belts that work well for you, you will be doing most of your work with the grinder.

You will see around knife 35 I finally figured out how to grind straight and completely horizontal. I am hoping by reading this it doesn’t take you as long. As the knife curves, pull the handle end away from the belt ever so slightly. (I want to emphasis the ever so slightly. Experiment and practice with this). It only takes a little practice to get this right.

When Grinding a Custom Made Knife pull the tip of the knife until it’s at the center of the belt, then pull away from the grind. Drawing the knife through the edge of the belt will result in a thinner tip than you want.

If your having issues, Slow the belt down if possible. Being able to slow down the belt speed greatly enhances ones ability to “feel” the grind and helps avoid mistakes. It also makes mistakes much smaller and easier to fix. Lastly, when a small mistake happens it forces you to regain focus.

If slowing the belt down is not an option then use very light pressure. Keep the knife moving in a completely horizontal slide. Then at the end, ever so slightly pull the handle end away to create the curve in the bevel.

Curving the knife to follow the bevel gives a different grind line and I believe it’s harder to achieve. Eventually you will want to master this technique as well but start using a straight and horizontal slide.

How far to grind the edge of the knife before sharpening.

One of the difficult pieces of information to find was how far to grind the edge of the knife before sharpening. After a lot of research and a bunch or trial and error I have finalized on this technique. I typically do the initial grinding before heat treating. You will read in a few instances where I did most of the grinding after heat treating and tempering, but typically I rough grind before heat treating.

For rough grinding you will want to leave the edge a little thick. David Boyle in his book “Step-by-Step Knifemaking You Can Do It” recommends leaving the edge .03” ¼” from the edge. A little thick means a bit more grinding after heat treat, but a few smiths feel it’s worth it to help prevent warpage during heat treatment.

After heat treatment you’ll want to get you’re knife ready for sharpening. But first, what “sharp” needs to be defined. That will be another post.

Grinding a Custom Made Knife tips:

- When you start Grinding a Custom Made Knife, start with an easy design. This is one without a shoulder, and with no curve or a small curve. (like knives 1 – 10)

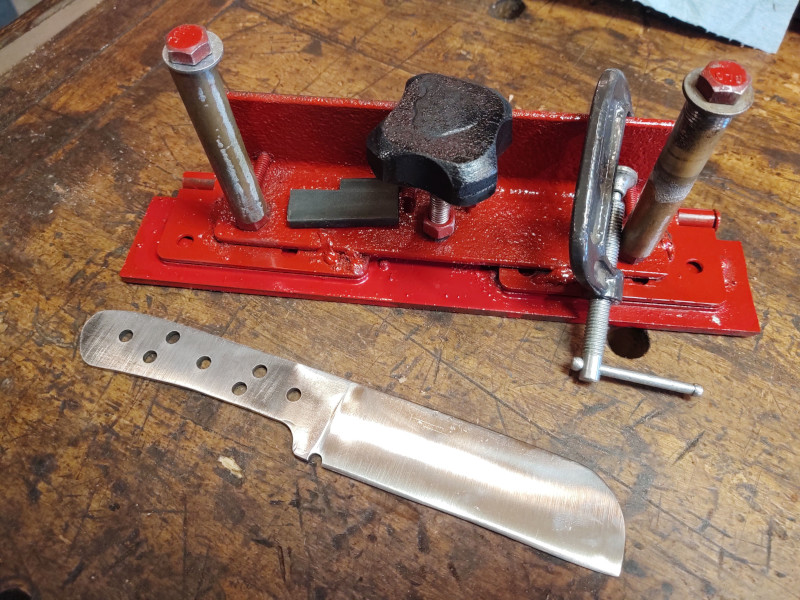

- Use consistent horizontal moves. A grinding jig will help until you’ve mastered freehand grinding. Since forming the bevel is the hardest, start each knife with the jig, and move to free hand. Slowly advance the move to freehand earlier and earlier in the grind.

- Buy quality belts from a repeatable knife makers supplier.

- If you are grinding after heat treating keep the knife cool buy dipping it in a bucket of water.

- Having good lighting is imperative to grinding well. You must be able to see your work, and as important, see the shadows. Make sure you have good lighting. A good movable light fixture is extremely helpful.

.

Alternatives to a belt Grinder

You can also use an angle grinder to get a rough bevel line. This is a bit harder to control for most, but if it’s what you have and you want to try it, with some patience and practice, it’s doable. Just stop early enough and switch to hand filing or hand sanding. You will be surprised how quick sanding with a 36 or 40 grit paper will cut annealed steel.

________________

As an Amazon associate, we earn income from qualifying purchases when you click on a link. Your link clicks help us fund our website.________________

[…] Grinding is here. […]

[…] make these knives I used the grinding jig for the bevel. The large choil (I’m not sure this term is being used technically correct, […]

[…] these knives when grinding the bevel, I found the best approach was starting at 36 grit, then going to 80 grit, then 120, 220 […]

[…] a left-over piece of 1095. The shape of the piece of steel inspired the knife. I also wanted to try grinding after heat treating before I did it on a full-size cleaver like Knife 30 – Cleaver and Knife 35 […]

[…] did this knife with all hand grinding (except for final hand sanding). I finally figured out how to grind straight and completely […]